Is a bowl of kale the same as a bottle of pills?

That’s not just a nutrition question-it’s actually a fascinating tax question.

Because in the eyes of the IRS, only one of those typically qualifies as a medical expense.

This is the heart of the debate around HSAs, FSAs, and tax-free healthcare spending.

The real question isn’t just “Is food medicine?”

It’s: When does a purchase cross the line from “generally good for you” to “medically necessary”?

That line matters—because only on one side of it are you allowed to pay without taxes. Physiologically, what we eat can dial disease risk up or down just as powerfully as many prescriptions. Financially, though, the tax code draws a bright line: until Congress or the IRS rewrites the rules, groceries remain groceries.

So before we imagine swiping an HSA/FSA cards for avocado toast, it helps to see how the courts have treated the idea over time.

Spoiler: they’ve mostly said “nice try.”

Yet the fact that people have been testing that boundary for decades (long before “Food is Medicine” was it’s own slogan) shows this tension isn’t new. So, when Americans have tried to treat their grocery receipts like pharmacy bills and write them off as medical expenses, how have the courts responded?

What the Courts Have Said

Estate of Webb v. Commissioner (Tax Court, 1958)

“Without Extraordinary Ruling”

Frankie L Webb was a women from Tennessee who, after learning of her hypertension, was prescribed a diet to address this medical condition. The diet included beefsteaks with kidney fat, avocados, pears, grapefruit, and potatoes cooked in a certain manner. Webb’s estate petitioned the courts that since this diet was (1) prescribed by a physician (2) part of her nutritional needs it should qualify as a medical expense and therefore be deductible.

However, the courts ruled otherwise. In their ruling the courts reference how this diet

(1) met normal nutritional needs (Webb allegedly ate this diet 3 times a day and didn’t consume anything else)

(2) Was without extraordinary food items or costs

(3) not supported by medical testimony

Cohn v. Commissioner, 38 T.C. 387 (Tax Court, 1962)

“Extra Charges Ruling”

Leo Cohn was a man from Indiana who suffered from recurrent heart failure. His doctor prescribed a salt-free diet for him. In order to conform to this diet, Leo could not add salt to his food and could eat only food that was processed and prepared without salt. Leo deducted $480 for taxi fares to restaurants which would prepare salt-free meals, and $840 for additional charges imposed to prepare salt-free meals.

The Courts ruled that those extra charges (above the normal meal price, and transportation to those meals) were a medical expense incurred by Cohn and thus deductible.

The precedent set here was that when a doctor-prescribed diet requires special preparation beyond a normal diet, the added expense can qualify as medical care. If the restaurant had not charged Cohn any additional charges for his prescribed meal, it would not have been deductible.

Harris v. Commissioner, 46 T.C. 672 (Tax Court, 1966)

“Normal Food Ruling”

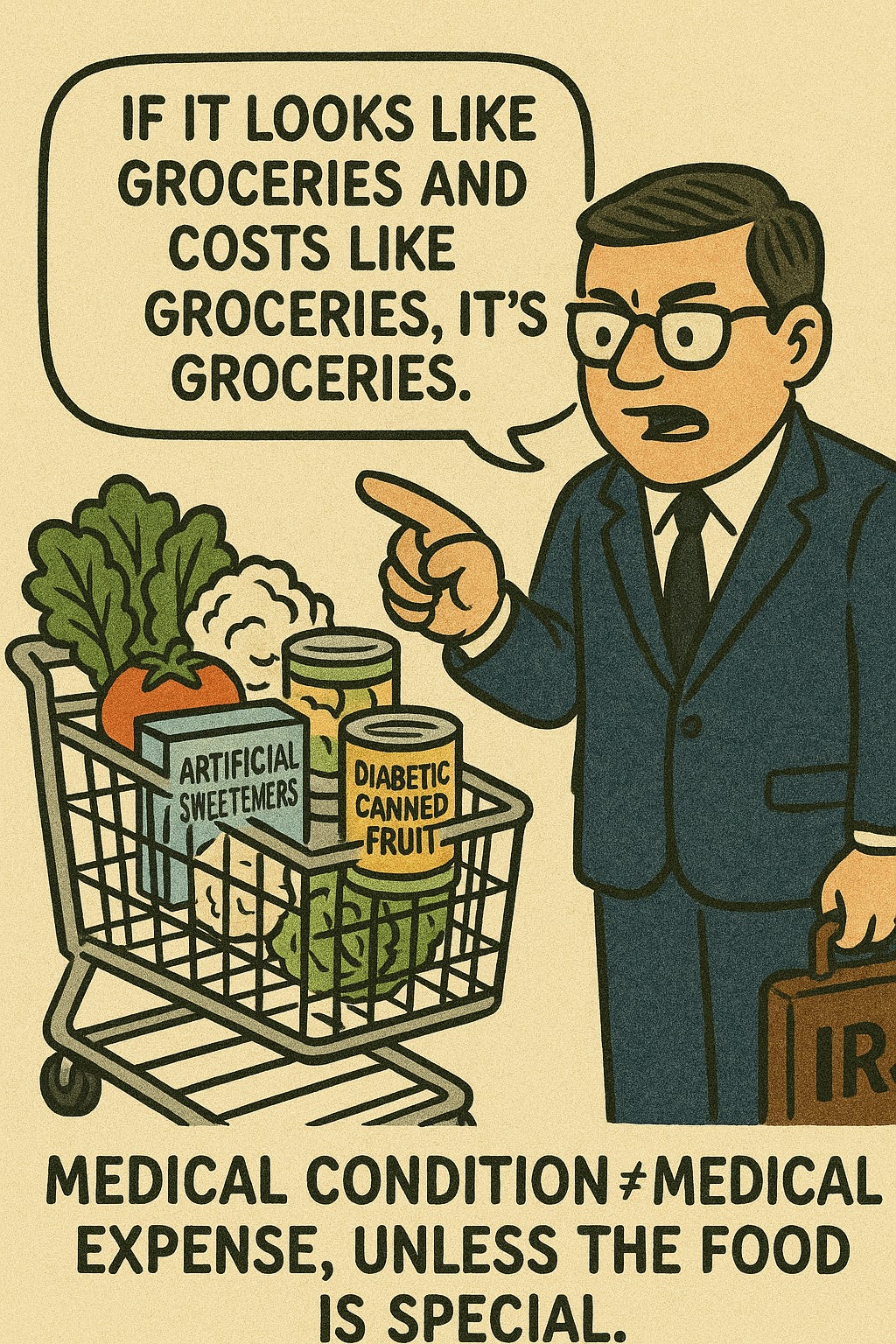

Gwen Harris was a woman from Illinois who was diabetic. As part of her medically prescribed diet, Harris purchased the following items and attempted to deduct them.

Artificial sugar- $41.88

Liquid sweetener- $23.28

Salt substitute- $9.36

Unsalted butter- $14.16

Diabetic canned fruit- $284.70

Diabetic salad dressings- $14.16

Salads (lettuce, tomatoes, cauliflower, and spinach)- $73.84

Total: $461.38

In their ruling, the court explicitly stated that

“We think it is apparent that the diet of a normal person is comprised, in part, of fruit, salad, salad dressing, butter, salt, and sugar. Thus, we would have no hesitancy in stating that the expense of petitioners in obtaining the special foods or food substitutes was a personal expense…

It seems to us that these diet foods must have been eaten in substitution for a normal diet, and it is highly likely that they were a source of nutrition.”

In this ruling the precedent is established that a medical condition alone doesn’t make regular food a medical expense-the food must be special in nature or cost.

Theron Randolph v. Commissioner, 67 T.C. 481 (Tax Court, 1976)

“Exceeds the cost of ordinary foods ruling”

Theron Randolph and his wife were allergic to a variety of chemical compounds found in pesticides and herbicides. To avoid severe allergic reactions, the Randolphs had to restrict their diets to chemically uncontaminated foods purchased from health food stores. Three unrelated physicians confirmed the medical conditions for both Randolphs. The Randolphs bought almost all their groceries at health-food stores, paying roughly twice the normal supermarket price. They spent $6,156.91 on organic items and claimed half of that ($3,086-the “extra” cost over conventional food) as a medical-expense deduction on their tax return. A comparison of retail food prices supplied by the United States Department of Labor, Bureau of Statistics, with sales receipts obtained from the health food store where the Randolphs buy 80 percent of their food, indicated that organically grown food is approximately twice as expensive as similar, chemically treated food.

The precedent from the Randolphs case was that these purchases were deductible because they met (1) a medical need, (2) the purchases were not meeting normal nutrition, (3) and cost of the food was above normal.

What must change before an HSA card works in the produce aisle

1. Congress has to amend §213(d).

Under current law an expense is “medical” only if it both treats a diagnosed condition and goes beyond “normal nutritional needs.” Until lawmakers revise that language-just as they did in 2020 for over-the-counter drugs, groceries remain nondeductible, and the IRS has no authority to say otherwise.

2. Any new statute will still echo the courts’ three-part test.

Decisions from Webb, Cohn, Harris, and Randolph all hinge on three criteria:

A documented medical condition.

Foods that are distinct from an ordinary diet (special formulation, higher cost, or required preparation).

Physician verification, typically through a Letter of Medical Necessity.

Loosen those filters and every routine grocery run would be tax-favored which is an outcome Congress is unlikely to accept.

3. Clinical documentation will remain the gatekeeper.

Even with a statutory change, expect the payment to clear only when supported by a physician’s letter of medical necessity.

Final Thoughts

It’s a fascinating tension for the government to try to strike with any of these changes.

Many in the wellness world point out that healthy food should be more accessible.

Yet it’s going to be hard to intelligently guardrail what food is properly eligible to prevent abuse.

Commentators who are worried about decreased tax revenue are laughable-

It assumes the government is entitled to tax everything, and any exception is a dangerous leak in the boat. But the foundational logic of HSA/FSAs is the opposite: that some purchases are so core to your well-being, it’s actually better for society (and cheaper for government programs) to not tax them.

Let’s say someone is pre-diabetic.

Scenario A: No HSA/FSA

They can’t afford a nutritionist or gym membership, so they skip it. A few years later, they develop type 2 diabetes. Now they’re on insulin ($300/month), regular doctor visits, lab work, and maybe even face complications like foot ulcers or kidney damage, all of which Medicare or Medicaid may eventually cover.Estimated long-term cost to the government: $200,000+ over their lifetime.

Example: Lifetime Cost of Type 2 Diabetes to the Government

(Assumes diagnosis at age 50, average lifespan to 75, and coverage under Medicare/Medicaid)

Insulin & supplies:

$3,600/year × 25 years = $90,000Doctor visits (PCP + endocrinology):

$1,000/year × 25 years = $25,000Routine lab work (A1C, renal panels, etc.):

$400/year × 25 years = $10,000Diabetes-related medications (e.g., statins, metformin, BP meds):

$1,200/year × 25 years = $30,000Complication management (wound care, neuropathy, eye exams):

$1,500/year × 15 years = $22,500Hospitalizations (e.g., infections, amputations):

$10,000 every 5 years × 5 = $50,000Estimated Total Lifetime Cost: $227,500

Scenario B: HSA/FSA-enabled

They use pre-tax dollars at age 50 (or earlier) to see a dietitian, join a gym, and buy a continuous glucose monitor. Let’s say they spend $1,000/year. Because it’s pre-tax, the government loses about $250/year in tax revenue.But they never develop diabetes. No meds. No complications. No dependency on government programs.

Estimated cost to the government: $250/year. That’s it.

Final math:

$6,250 in preventive tax breaks

vs.

$227,500 in downstream disease managementThat’s a 36:1 return on prevention.

Let’s get a return on prevention